CLXXXIII. STOCKHAUSEN, Karlheinz (1928-2007)

Zyklus (1959)

Alexander Smith, percussion

(9:44)

I was 15 and drove everyone in my family crazy when I played this album -- one of the most important musical discoveries of my life.

There are two ways of listening to this music:

- As I did, when -- as a 15-year-old musician -- I became intrigued and fascinated by these new sounds I heard, which transcend every other type of music most people have ever heard; nirvana, if one just allows one's ears to open up and allow the air molecules to coalesce and transfix; or

- One can study Stockhausen's lengthy texts on the details of the composition and performance(s); then -- with a hopefully clear understanding of the composer's intentions -- listen as in 1) above, with the added clarity of gained knowledge.

There are many people who feel as I do -- that Karlheinz Stockhausen is one of the greatest composers of all time -- but there are many more who simply can't hear anything but noise. [Noise is music.]

Stockhausen's text:

Stockhausen's text:

**

ZYKLUS = CYCLE

In 1959, I proposed to the director of the Darmsteadt Vacation Courses for New Music, Wolfgang Steinecke, that percussionists be included as soloists in the Kranichstein Music Competition. He was enthusiastic and asked me to compose -- as the compulsory piece -- a work for a solo percussionist. I wrote ZYKLUS for a percussionist and dedicated it to Wolfgang Steinecke.

Christopher Caskel performed the world premiere in Darmstadt on August 25, 1959 in the opening concert of the vacation courses. Numerous aspirants to the Music Prize for Percussionists performed in front of a jury, Heinz Haedler winning the 1st prize. Since then, ZYKLUS -- the first solo composition for an extensive array of percussion instruments -- has become the show-piece for percussionists in examinations, competitions, chamber and solo recitals. Numerous gramophone records and CDs of ZYKLUS have been released.

**

The title ZYKLUS has the following meanings:

- The large form is a cycle of 17 periods, which are printed on 16 spirally-bound pages. The player prepares a version, which may begin with any period, then plays a complete cycle in the given order, ending with the first sound on the initial period. It is possible to turn the score upside-down and read all the pages in the reverse order. The periods should all be of equal length. Each period is divided into 30 time units of equal length, the duration of which may be decided by the player. In many interpretations, the tempo MM 44 has proven favourable: 17 x 30 = 510 units, multiplied by 1.36 seconds makes 695.5 seconds or about 11 minutes 36 seconds ... many experiments have been made by various percussionists to keep the durations of the 17 periods constant. The American Max Neuhaus [the performance recorded in the album pictured above, as I heard as a 15-year-old!] practised for months using a stroboscopic lamp, the periodic blinking of which could be varied at will. Other percussionists rehearsed with a tape recording of their own voice counting the metronomic time scale in varying bars ... The 17 periods are characterised by 9 dominating timbres, whereby in every second period an instrument or a type of playing arrives at a maximum (snare drum--hi-hat--triangle--etc.). After its maximum, a dominating timbre becomes ever rarer in the succeeding 8 periods (ritardando), and in the 8 further periods, gradually appears more frequently (accelerando) ... the following table shows these 9 dominating instruments and their 9 attack-cycles in the 17 periods ... the falling and climbing lines indicate ritardando and accelerando, and the progresions of the time intervals between the attacks in the 9 attack-cycles are indicated as musical intervals (which must be imagined as time-intervals: major sixth 4√8, major second 6√2, etc.)

The notation of the 1st period [of the Caskel version], with the maximum of the snare drum and the first 7 rim shots of the tom-toms during the ritardando in the 41 attack-cycle, looks like this: - Nine temporally fixed attack-cycles thus form the permanent skeleton of the 9-layered ZYKLUS. These are divided into 2 semi-cycles by variable events, whose order and moment of performance may be varied, and inserted between the fixed attack-cycles by the interpreter. These variable events occur as 9 structure-types, ranging from regular-unequivocal to statistic (aleatoric)-ambiguous.

An example of the regular structure-type 1 is the 1st period of the Caskel version; regular ritardando (snare drum and rim shots), countable groupings:

The statistic (aleatoric) structure-type 9 reaches its extreme in the 17th period of this version:

The 17 periods in the order of the Caskel version are divided into two semi-cycles by the 9 structure-types in the following way:

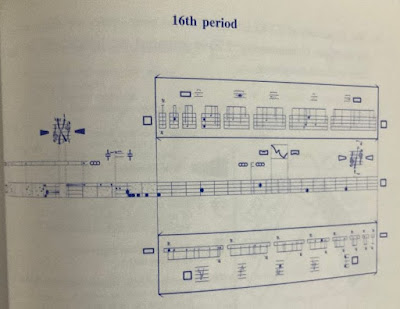

Thus, the 1st, 9th and 17th periods are undivided. To help clarify how the other periods are sub-divided by structure-types, several periods of the score are reproduced here:

13th period14th period

15th period

16th period - The 17 periods of ZYKLUS and the two semi-cycles are characterised by timbres (instruments). I have arranged the instruments so that they encircle the player.I had already introduced 6 African wood drums into percussion music in my GRUPPEN for three orchestra (1955-57) -- after having discovered them in the Museum of Ethnology in Cologne. Likewise, since GRUPPEN, I integrated 3 x 4 tuned tom-toms, 3 tuned snare drums, and 13 tuned cow bells as instruments of music.

Tuning of the wood drums, tom-toms and cow bells with 4 adjacent pitches of the scale (if possible, tune tom-toms to the 4 lowermost pitches):

The number of instruments used for the variable events in the 17 periods (in the order of the Caskel version) increases and decreases twice:

In the variable structures, vibraphone and marimba, which are also used with glassandi for the 9 skeleton cycles, have groups and single pitches (no glissando-like figures). The same applies to the snare drums: in the fixed cycles it always has rolls, in the statistic (aleatoric) structures it has only groups and single strokes.

The order of the instruments in which they successively enter and -- after 5 periods each -- exit, is:

Thus, during the course of a performance, the main position of the player rotates either counter-clockwise or clockwise (depending on the direction in which he reads the score for his version). - The succession of 5 maximum dynamic levels and 5 intensity-forms is regulated by the skeleton-cycle of the tom-tom rim shots (always ff).

12 degrees of intensity are indicated in the score by the size of the note heads:

The 5 intensity-forms are as follows:

1) generally soft with a few peaks of the maximum intensity,

2) intensity varied from attack to attack (pointillistic),

3) intensity changed group-wise,

4) crescendi and descrescendi (through-composed),

5) constantly maximum intensity.

Thus, the two specifications: maximum intensity and intensity-form change with each rim shot.

Starting with the 1st period of the Caskel version, the intensity changes from rim shot to rim shot as follows: - Finally the intervals within which the frequencies of the pitched attacks occur (vibraphone, marimba) are also cyclic. Each glissando comprises such an interval, and all the pitches occurring before the next glissando fall within its range:

Exceptions are clearly recognisable single pitches jumping outside of these intervals, and in the 7th period, the second widest range is combined with the narrowest interval (trill of the vibraphone):

In order to compose the relationships described between the sounds and noises, I had to employ a relatively large number of percussion instruments (9 variously conspicuous instruments which are used only for the variable form elements). To do this, I necessarily had to choose instruments which were quite difficult to acquire, for instance African wood drums (log drums), cow bells, nipple gong -- all chosen according to specific pitches. My choice, therefore, was an ensemble of percussion instruments which I could find in 1959. Some of the instruments are primitive, and if it had been possible I would have integrated others, especially more percussion instruments having specific pitches. Thus, the composition of timbres is relative: I can imagine that the function of the sounds in the form described here could also be realized with other timbres, as long as the varying complexity, the different degrees of the resonating and non-resonating bodies of sound, the scale of the more or less memorable clarity and conspicuousness is taken into account and refined. However, it does not make sense to replace particular prescribed instruments by less refined ones, as has often happened. For instance, one interpreter replaced the cow bells which should resonate as long as possible with as many partials (overtones) as possible and one main pitch -- which does not have to be the fundamental -- by the very dull and unresonant cencerros. Or, instead of the quite low and fully resonant wood drums, someone used temple blocks; instead of the nipple gong, little psuedo gongs or tam-tams, etc. The use of instruments other than those prescribed should only take place if -- by this replacement -- the form becomes clearer and the overall sound more refined.

Some percussionists have attempted to perform directly from the printed score. I have never heard a successful recording or performance done in this way. On the contrary, I recommend all percussionists to study the structure and meaning of each element, and then -- corresponding to their conclusions -- to make a version by photocopying the score, cutting it apart and pasting the variable elements into the fixed skeleton cycles. It is necessary to practice such a version to perfection, and to play it from memory if possible. Then, after several performances of a version, details can be changed or a new version can be made.

No comments:

Post a Comment