CCCLII. BEETHOVEN, Ludwig van (1770-1827)

Beethoven always had a stormy relationship with his publishers. Artaria was no exception; an argument over the String Quintet, Op. 29 had to be settled in court.

Nevertheless, they obviously kissed and made up, as Artaria published the Hammerklavier piano sonata (see Post CCV] as well as this quartet.

**

Beethoven struggled to finish Op. 130 for many, many months. He had already written the first five movements, when he embarked upon a finale that he probably felt was meant to be the Finale of all time!

He had always wanted to compose a work utilizing Bach's initials (B-Flat, A, C and B-Natural in German musical nomenclature) ... but eventually decided against this in favor of a similar fugue subject:

Compare the BACH motif:

with the ultimate fugue subject Beethoven settled upon:

The public reception to this quartet was astonishing (combined with astonishment).

But -- unlike the Ninth Symphony (see Post C) -- there was no hint of what was to come after the earlier movements. The audience was befuddled by the massive double fugue (see Post CXLIV -- the Grosse Fuge, Op. 133) and two events occurred which would convince Beethoven to replace this Finale with a new one:

- First, Artaria asked Beethoven to publish a four-hand version for piano, which LvB agreed to, but handed off the task to one Anton Halm. The results were unsatisfactory as far as Beethoven was concerned (he didn't like the way Halm had divided the parts), so he did it himself -- for a new fee; and

- Secondly, Beethoven quickly agreed with Artaria's request to provide a new Finale for this work -- and took another fee for the publication of Op. 133 as a separate work -- and wrote a new finale that turned out to be his very last fully completed composition before his death.

a dactyl skipping rhythm:

an intense, accented unison (brown); tiptoeing up the stairs (pink) and a new theme in G-Flat Major (green):

and now six tempo changes: slow/fast/slow/fast/slow/fast; D Major to G Major; the theme is presented and shortened.

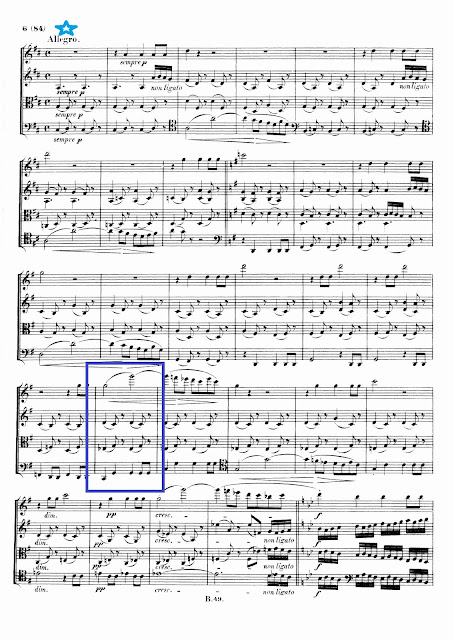

Since I was a kid I have been obsessed with the chord highlighted in the blue box: It's a jazzy chord: a C Minor Ninth (the D is in the second violin)!

and again the six tempo changes in the Coda:

Second Movement

A presto dance in the parallel minor. Note how the four-note motif adds three additional 1/4-notes after the repeat:

Again the creeping up the stairs motif, followed by sliding-down-the-slide:

Third Movement

First, let's try to decipher Beethoven's tempo indication:

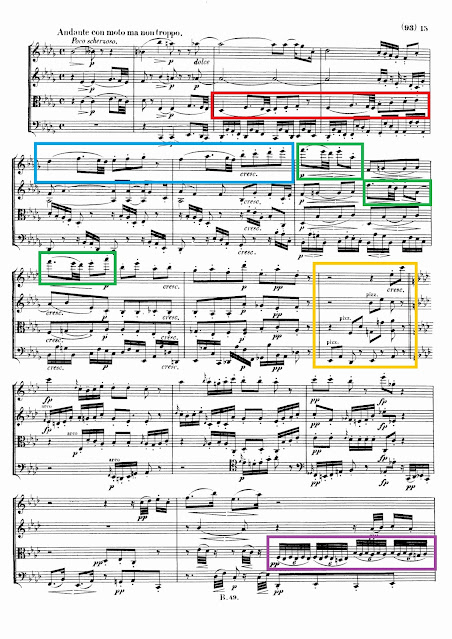

Andante con moto (slowly with motion), ma non troppo (not too much) and then in italics underneath: Poco scherzando (a little jokey) ...

So let's look at the first two bars in this reduction:

The motion begins with staccato 16ths in the cello accompanying a gorgeous melody which moves from viola (red) to violin (blue); Beethoven shortens the motif (green) and prepares a theme variant with pizzicato (orange).

The movement concludes with a flurry of 32nd-notes. a quick pause, and a satisfying fifth-less tonic chord.

Fifth Movement

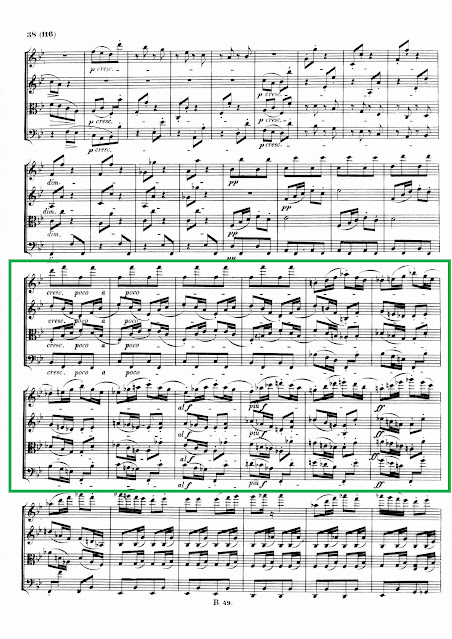

Let's look at it:

This is Haydnesque, as if Beethoven was reliving his early days in Vienna circa 1800:

and a satisfying finish with a 12-note tonic cadence!

No comments:

Post a Comment